CDI Delegates Conduct the Feasibility Study on the Establishment of Special Economic Zone in Sindh

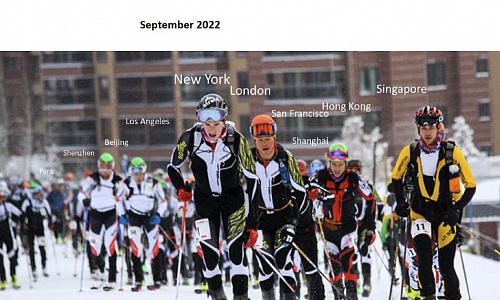

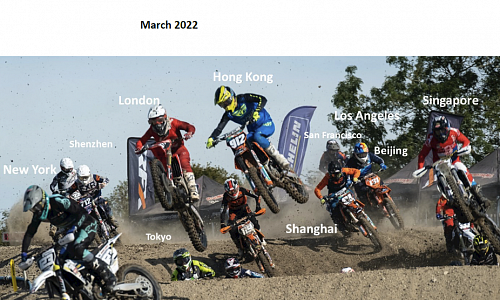

CPEC is high on the agenda of the Belt and Road Initiative. Having improved road, rail and air transportation, CPEC now shifts to boost the project of special economic zones which will bring industry and investment to Pakistan. Motivated by the success story of Shenzhen, Pakistan will establish nine special economic zones.

Belt and Road: The Economic Rationale

Author: Fan Gang, President, CDI

Author: Fan Gang, President, CDI

Editor’s Note: At the Belt and Road: Seize the Next Wave of Growth in Eurasia forum on November 23 in Venice jointly held by China Development Institute and The European House – Ambrosetti, Professor Fan talked on the economic rationale of Belt and Road. Here are excerpts from his speech:

There are lots of questions about how China will benefit from the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The usual analysis is from international diplomacy and geopolitics point of view, which states that by improving infrastructures and connectivity, China gains a bigger market, resulting in more investment in neighboring countries and the world. This is undeniable.

But as an economist, I would like to stress the importance of the economic rationale of BRI. People may wonder why China has the money to finance BRI since China is still poor – GDP per capita is quite low comparing with developed countries. But after 20 years of high savings, China accumulated wealth. The question lays in how to use this saving. If invested in domestic economy, over capacity is inevitable. Currently the surplus goes to foreign exchange reserves, which goes to US treasury bonds. But why not invest in concrete projects that can facilitate other countries’ development, strengthen connectivity with China, and also build our community for future prosperity? Therefore, economically speaking, BRI is a better way for China to utilize its national saving.

However, BRI can only be fulfilled by a joint effort by China and other countries. Although the main focus is infrastructure investment, we should not only calculate cost and benefit in terms of direct return or short-term returns, but also the future, the return to public good, and the economic prosperity of the region.

Nonetheless, it is still investment which requires us to consider carefully about financing and selecting the projects, compatibility with local country’s economic development strategy, effectiveness and efficiency of the projects, which essentially amounts to how to succeed and benefit the people in the future. These are the questions we bear for the Belt and Road: Seize the Next Wave of Growth in Eurasia which is also why I think holding this forum is important.

Narrowing the External Imbalance

Growth remained stable in November, with industrial output up 6.1% y/y. Fixed asset investment excluding agriculture was up 6.3% y/y, up 0.5 pps from October, and up 2.4 pps from its August nadir. However, the current investment growth rate is still lower than investment goods’ price growth rate, indicating that real investment growth is still negative, by -0.2% y/y.

Growth remained stable in November, with industrial output up 6.1% y/y. Fixed asset investment excluding agriculture was up 6.3% y/y, up 0.5 pps from October, and up 2.4 pps from its August nadir. However, the current investment growth rate is still lower than investment goods’ price growth rate, indicating that real investment growth is still negative, by -0.2% y/y.

National fiscal revenue fell -1.4% y/y, turning negative for the first time this year. Since current investment strength is mainly government driven, the fall of fiscal revenue will constrain a possible investment rebound. Retail sales of consumer goods were up 10.2% y/y in nominal terms in November, the same rate as in Q3. The consumption indicator is always very stable. The ex-factory price index of industrial output was up 5.8% y/y in November, and PPI was up 7.1% y/y, down 1.1 and 1.3 pps respectively from October, indicating that price appreciation since August represents only a temporary rebound.

M1 was up 12.7% y/y by the end of November, down 0.3 pps from the end of October, showing a consecutive downward trend. Deposits from non-financial enterprises rose 11.9% y/y, down 0.5 pps from the end of October. M2 rose 9.1% y/y, slightly higher than the lowest level, up 0.3 pps from the end of October, mainly affected by large increases from fiscal deposits and non-bank financial institution deposits.

Exports were up 12.3% y/y in November in dollar terms, and up 5.4 pps from October, outstripping the fastest growth rate of Q2. But we believe the fast export growth rate is likely an outlier.

Imports maintained their strong growth, up 17.7% y/y, and up 3.1 pps from Q3. Even conservatively speaking, we expect China to surpass the United States as the world’s largest importer in 2022. Consumption demand as a rising share of import increase will be a key opportunity for investors. This is part of the effort made by current Chinese leaders to further integrate with the rest of the world, and to curb China’s external imbalance, with such initiatives as the Road and Belt, and AIIB. China will also hold its first annual national “import expo” in 2018. By contrast, U.S. President Donald Trump seems to be moving in the opposite direction, most recently seen as threatening to withdraw foreign aid, simply because countries do not support his decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Any withdrawal by the United States will give China room to expand its role in world trade.

The 10th Shenzhen-Hong Kong Forum

Information

Date: December 7, 2017

Venue: Pengcheng Hall, Qilin Villa, Shenzhen

Host: CDI, Central Policy Unit of HKSAR

Theme: Shenzhen-Hong Kong Cooperation to Drive the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area

Belt and Road: Seize the Next Wave of Growth in Eurasia

Information

The forum is focused on mutually beneficial strategies and investment opportunities sparked by the Belt and Road Initiative that will catalyze development and new industrial activities all over Eurasia (China, Central Asia, Middle East, Europe).

Date: November 23-24, 2017

Venue: Ca’Vendramin Calergi, Venice

Organizer: China Development Institute, The European House – Ambrosetti

Theme: Belt and Road: Seize the Next Wave of Growth in Eurasia

Financing the Development of the Belt and Road: Key Challenges

Author: Wang Jianye, Managing Director, Silk Road Fund; Professor of Economics and Director of the Volatility Institute at NYU Shanghai; recently has been selected as Rotating Secretary General of the International Working Group on Export Credits (2020-2023).

Author: Wang Jianye, Managing Director, Silk Road Fund; Professor of Economics and Director of the Volatility Institute at NYU Shanghai; recently has been selected as Rotating Secretary General of the International Working Group on Export Credits (2020-2023).

Editor’s Note: At the Belt and Road: Seize the Next Wave of Growth in Eurasia forum on November 23 in Venice jointly held by China Development Institute and The European House – Ambrosetti, Professor Wang talked on the financial issues and challenges that Belt and Road Initiative faces.

Over the three years since the launching of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), from an investment and financing perspective, what have happened? What have we learned? What are the key challenges going forward?

What have happened?

It has almost become a cliché that the vast landmass in the Eurasia continent, with growing population and markets, has great growth potential. Investment to increase connectivity in this not well-connected region would expand the market, creating effective demand and growth. However, while officially-supported institutions increased their financing, we have not yet seen large capital flows into the developing countries in this region. Why?

A recent World Bank research is telling.1 Their data show that per capita investment growth in emerging market and developing economies has been falling rapidly since 2010, with non-BRICS commodity exporters from roughly 7 percent in 2010 to 0.1 percent in 2016. This is in contrast to the partial recovery in developed economies. By 2014, investment growth there had returned to its long-term average rate, about 2 percent. Their research points out that sluggish investment and growth in developing countries, notwithstanding record-low external borrowing costs and large unmet internal investment needs, can be attributable largely to domestic problems – worsening business environment, rapid buildup of enterprises debt, and policy uncertainty – while external factors such as major countries’ economic slowdown also played a part.

Against this background, let’s look at data from China. Three developments are worth noting from China’s international investment flow data of the last few years:

First, outward direct investment (ODI) increased dramatically in 2015-2016, driven largely by private enterprises. ODI since the global financial crisis could be divided into two periods: 2008-2013, 2014-2017. Data compiled by government and market sources indicate that private sector drove the recent outflow acceleration. ODI relative to GDP rose from 1.1 percent in 2014 to 1.5 percent in 2015 and 1.9 percent in 2016.

Second, destination markets also shifted from emerging and developing economies to developed countries. It should be noted that ODI by disclosed value and number of deals in the Belt and Road developing countries have also increased, admittedly from a very low basis. In conjunction with the rise of the private enterprises, ODI target industries experienced a shift, from primary commodities to services, high value-added manufacturing, and consumption related sectors.

Third, the recent surge in capital outflows especially in 2015-2016 reflects to certain extent masked capital flight. Unusually large and rapid buildup of foreign assets by some domestic entities through M&A or purchases in real estate and unrelated businesses became a source of concern. Some entities including in the financial industry accumulated large domestic liabilities in support their foreign spending spree, increasing balance sheet mismatches. “Errors and omissions” in the balance of payments were also indicative of such a flight, which increased from -0.6 percent of GDP in 2013-14 to about -2 percent of GDP in 2015-16.

The regulatory authorities responded by strengthening the enforcement of capital flow regulations and domestic financial prudential requirements. Starting from November 2016, irregular ODI has subsided. Recent BOP data suggest that net direct investment, which turned deficit in 2016, returned to small surplus in the first three quarters of this year.

What have we learned?

Financing the development of the Belt and Road has to be on market principles. Multiple factors affect China’s capital flows, but primarily market forces in the international arena. Our analysis points to three types – cyclical, structural, and governance drivers. Cyclical forces stem from changing expectations on domestic vs. foreign interest rates and exchange rate movements. Structural forces result from rising domestic costs—wages, land prices, tightening of environment regulations, etc. Governance factor affects SOE investment through corporate governance; it also affects private investment through its impact on uncertainty regarding taxation, regulatory treatment, and property rights protection. In opening up its financial account, China faces domestic financial stability constraint.

The principles of sharing are very important for BRI financing sustainability. The BRI is not a “Marshall Plan,” and cannot be a one-actor show. To achieve “win-win” outcomes, in May 2017 finance ministries of 26 countries endorsed the Guiding Principle on Financing the Development of the Belt and Road, highlighting “equal-footed participation, mutual benefits, and risk sharing.”

Challenges going forward.

First, the leadership challenges to state-owned enterprises. As the Chinese economy is in transition, SOEs still play dominant role in some sectors and significant in others. SOEs’ return on assets and investment return have been falling in recent years, and significantly below that of private enterprises. According to the IMF, adjusted for implicit support through the use of land and natural resources, and lower implicit financing cost, SOEs’ return on equity is estimated to have become negative since 2012.2 In the industrial sector, SOEs account for more than half of corporate debt and 40 percent of industrial assets but less than 20 percent of industrial value added.

Returns on SOE overseas investments are likely to be much lower on average than private enterprises. These companies, especially their leadership, are facing daunting challenges to increase efficiency and profitability. For cross-border M&A, more important is post-acquisition restructuring and management. Strategic vision, efficient decision making and high-quality execution are vital, which require sound corporate governance, market consistent incentives and market-driven corporate culture to attract and retain talents. All are leadership demanding.

Second, the challenges for direct investment in developing economies in the Belt and Road. Many countries are low-income, small size, placing viability limit on projects that require larger market. Red tape and rent-seeking also add to the hidden costs of doing business there. Moreover, counterparty risks are high. It is often difficult to find local corporate partners with solid balance sheet and performance track record. Payment capacity is typically a concern with high risks over the longer term. Few countries or companies there are in investable credit rating. Many are vulnerable to global and commodity cycles.

Coping with these risks would require our enterprises operate on market principles, thoroughly understand local conditions, and on that basis match investors of various preferences for risks and returns with the right projects and other partners. Special attention should also be paid to social responsibilities and environmental protection. Building alliance with local stakeholders and going green would help achieve commercial success in the relatively risky segments of the market.

Third, the challenge of expanding the use of RMB in overseas direct investment. In the last several years, large ODI and other capital outflows have led to a decline in China’s foreign exchange reserves from nearly $4 trillion to slightly over $3 trillion. At this stage, maintaining a sizable official reserves before the RMB exchange rate can be freely floating is important for financial stability. Expanding ODI thus would entail the use of RMB. Although the RMB has become a composite currency of the SDR, its share in World foreign exchange transactions is still smaller than several currencies that are not in the SDR basket.

The challenges are to progressively develop the relevant infrastructure, reduce RMB funding and holding costs, build up so-called “network externality” (i.e., a greater number of users increases the value to each). Of course, international use of a currency depends ultimately on market acceptance, which could be a long process. Stable currency value and the rule-of-law institutions and governance are therefore fundamental.

Finally, the challenge to modernize governance at home in face of increasingly free cross-border mobility of capital and talents. Public sector reforms are particularly relevant in this regard. Exposing the SOEs fully to market competition through opening up protected sectors and removing implicit subsidies would force restructuring, increase efficiency, and contribute to leveling the play field for all enterprises.

Fiscal reforms to make public spending accountable, reduce uncertainty in taxation, and realign central-local fiscal relations will go a long way in instilling confidence and reducing capital flight. Reform to make the tax system more progressive will not only help alleviate income inequality, but also put the public finances on a more sustainable footing, good for internationalization of the RMB.

The recent State Council Opinion reiterated that effective protection of property rights is a cornerstone of our society. The challenge is not just in implementation, but in the difficult institutional and cultural transformation to a “rule-of-law” society.

The BRI calls for “opening-up” of the countries in the Eurasian continent. In doing so, it also creates the conditions for institutional and governance modernization in these countries. Real progress in these reforms will not only transform the business community but also the relevant society, benefiting people along the Belt and Road, creating truly “win-win” outcomes.

------------------------------------------------

1 Ayhan Kose, Franziska Ohnsorge, and Lei Sandy Ye, 2017. “Weakness in Investment Growth: Causes, Implications, and Policy Response.” Policy Research Working Paper 7990, World Bank, Washington DC.

2 International Monetary Fund, Staff Report for 2017 Article IV Consultation, paragraphs 18-19, http//www.imf.org.

Experience of London Financial Centre

Author: Mark Yeandle, Associate Director, Z/Yen Group Limited

Author: Mark Yeandle, Associate Director, Z/Yen Group Limited

Editor’s Note: At the China Industrial Finance Forum 2017 on November 17 in Jinan held by CDI, Mr. Mark Yeandle shared his views on the experience of London financial centre. Here are excerpts from his speech:

Firstly, was the city of London constructed or did it grow? What keeps it as an important center? Secondly, is there any lesson we can learn from the development of Canary Wharf from scratch? Thirdly, if there is any lesson for China’s financial centres?

London was not planned as a financial centre. It developed as a trading centre of a very successful empire. The British people always had a long history of international trading. Then we had the industrial revolution and the building of financing as an industry which had a massive impact on the country. It became a very logical sequence if you carry on building financial centres. Big bang in 1980s was a deregulation of financial services which freed up the market and allowed the UK and London in particular to grow and thrive. The invention of modern finance, the industrial revolution and the Big Bang are the three great steps of innovation.

Obviously, London is a big city in terms of the size and population. Interestingly, long-term decline of sterling actually helped Britain more international. Investment managers could make good returns in investing purely in UK instruments simply because the value of sterling was dropping. Constant innovation, the development of institutions over the years, being one important centre in the European time zone which enables London to speak to Asia and America in the same working day, English language, skilled people, general reputation of trustworthiness, all sort of things all helped London develop.

Why does London stay on top? Time zone and English language are still important. Liquidities of market are now so strong. London has become a leading centre for stocks, shares, bonds, foreign exchanges, derivatives, insurance, etc. It got all the intuitions like the Lloyds insurance market and the Baltic Exchange. Innovation, like Fintech, also helps London stay on top.

How on earth did Canary Wharf come about? It is now a leading financial area and 30 years ago it was still part of the London Docklands. The London Docklands actually died in the earlier part of this century. Thames were tidal so you always got ships up and down. The harbours basically died because long ships were just too big and deep for the city. So, we ended up with Canary Wharf as an industrial wasteland very close to the City of London. The City of London is one square mile and it is just contained within the old Roman Walls, so it is very limited in space. The old financial development tried to take place there but there was simply not enough room in the City. The buildings were very old and unsuitable and quality of office environment in London was poor. So, the Docklands development organizations went to the City of London and asked: “are you happy with your office premises or do you see the need to do something dramatic?” The answer is that we have to do something dramatic.

Canary Wharf was not planned. It was there because it was demand. I have been to many financial centres where premises have been built early in the process. They have very lovely glass towers, very shining and impressive. Unless you plan early on how to fill them, they will become embarrassment when you leave them empty there. Canary Wharf was filled basically before it was built, because there was so much demand there. The development worked very closely with London about transport links because Canary Wharf is still far away from the City. They spent huge amount of money on transport, like Jubilee Line, City Airport, Docklands Light Railway, London River Services and Helipad.

What perhaps China’s financial centres can learn from this? Building a financial centre, you start with business environment and sufficient infrastructure. Only when you get those two things, skilled people want to move in and financial sectors begin to develop here. Eventually, it will lead to the reputation as a strong financial centre. The generalities of financial centres also give some advice. You cannot be an international centre without international people. Successful people want to live in successful cities. People want to live in cosmopolitan places and gravitate to cluster of their industries. Reputation of the centre is vital because it takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it. Trust is the glue that holds all relationships together. People will not come to and invest in the city, unless they trust that they will be treated fairly no matter where they come from.

Dr. Qu Jian Attends Sino-Kuwait Strategic Cooperation Seminar

China Industrial Finance Forum 2017

Information

Venue: Shandong Hotel, Shandong, China

Organizer: CDI, and the Financial Office of Jinan Municipal People’s Government

Theme: Industrial Finance to Support Real Economy

CDI International Report on Economics of the Anthropocene

Information

Venue: Room 101, CDI Mansion, Shenzhen

Host: CDI

Theme: Economics of the Anthropocene: Principles and Consequences for Policy Design