The Most Innovative City in China: Shenzhen’s Model for Innovation-Based Economic Growth

Click here to download the full report

Date: November 2024

Author: Prof FAN Gang, President of China Development Institute; Dr CAO Zhongxiong is Assistant President, and Director of the Digital Economy and Global Strategy Research Department of China Development Institute. E-mail: caozx@cdi.org.cn

Shenzhen, reputed as China’s technology capital and a global manufacturing powerhouse, has undergone an astonishing transformation from a small fishing village into an international hub of innovation in a mere 45 years. Home to global giants like Huawei, Tencent, BYD, Dajiang-Innovation and BGI Genomics, the city also nurtures a thriving ecosystem of startups in emerging fields such as biotechnology, artificial intelligence (AI), hydrogen energy and the low-altitude economy. Shenzhen stands as a testament to the wonders of urban development and represents a typical example in global technological innovation and industrial progress.

Diversified development infuses the city’s industries with vitality. Shenzhen’s urban growth initially hinged on a cluster of open industrial parks that attracted manufacturers from Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan and elsewhere. However, the city did not rest on its manufacturing successes. Amidst the sweeping global trends of industrial relocation and innovation, Shenzhen has persistently fostered new industries and tapped into the intrinsic momentum driving urban industrial advancement. For instance, Shenzhen’s pillar industries have evolved from outsourced processing and export-oriented manufacturing, and logistics supply chains to high-tech and strategic emerging industries. Today, Shenzhen is even more proactive in cultivating industries of the future, such as quantum computing and graphene. Furthermore, the city’s industrial development places a strong emphasis on the seamless integration of both new and traditional growth drivers. Building on the foundations of traditional industries like bicycles, gold jewellery, women’s fashion and shoes,…

How Can Beijing and Brussels Move Forward with Their Trade Relationship Amid Geopolitical…

Click here to download the full report

Date: May 25, 2024

Author: WEI Fulei, Director, Centre for Finance, Trade and Industrial Development, China Development Institute

China and the EU, as two of the world’s major economies, together comprise one-third of the global economic output. China is now the EU’s second-largest trading partner, as well as the largest source of its imports and the third-largest destination of its exports. In recent years, the EU has accelerated the ‘de-risking’ process amid geopolitical crises, and prioritised security in the cooperation with China, a shift from the past orientation towards economic interests and technical cooperation. A raft of new acts and policies adopted by the EU, in particular the Critical Raw Materials Act, has challenged China-EU relations. Nevertheless, the two economies are still highly complementary in terms of industrial structure, technological strength, and market demand. As reiterated by Wang Yi, Member of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Foreign Minister of China, China and the EU are comprehensive strategic partners with common interests far outweighing differences, and cooperation is the keynote of China-EU relations.1 In the future, China and Europe should strengthen dialogue, enhance strategic mutual trust, bolster consensus on cooperation and development, and collaborate to facilitate trade cooperation under the new and turbulent circumstances.

BRI Projects in ASEAN: Implementation, Mechanism and Suggestions

Click here to download the full report

As a key strategic partner of China, ASEAN is an important participant in the development of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). ASEAN has made a commitment to link its Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity 2025 with the BRI and accelerate its infrastructure development on the great momentum brought about by the BRI. At present, the BRI has achieved general strategic alignment with ASEAN countries.

Beyond Greater Hong Kong: Is Shenzhen emerging as a global city with distinct cultural roots

Click here to download the full report

Executive summary

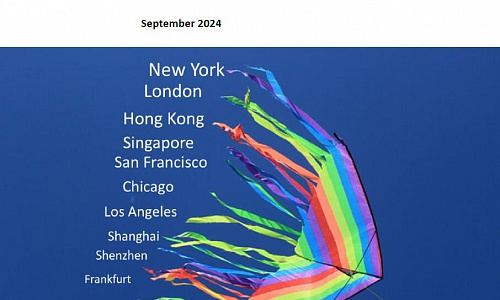

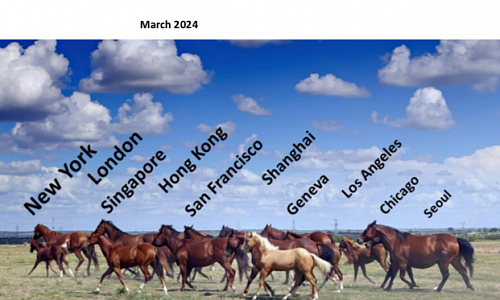

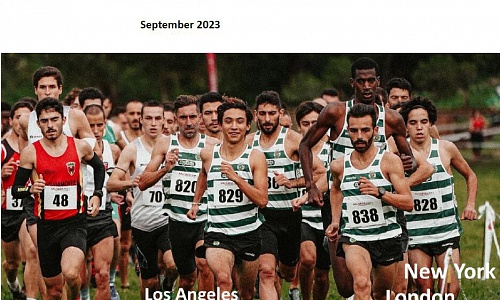

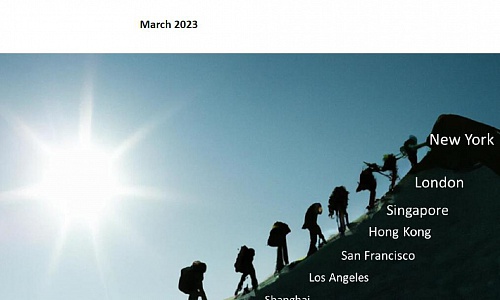

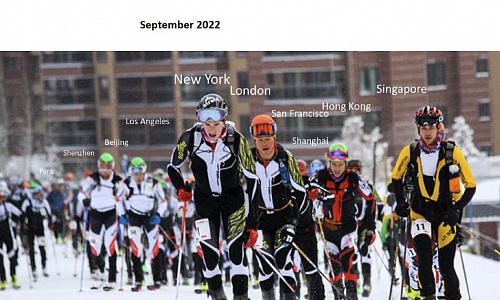

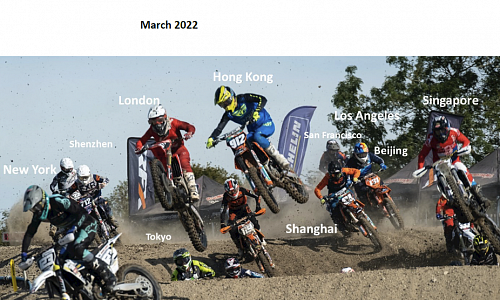

After the obsolescence of the ‘Greater Hong Kong’ narrative dominant in the 1990s, today Shenzhen is recognized as an emergent global city of its own. Yet, at the same time important indicators of this status are still ambiguous, such as the role in international financial flows or the dynamics of its service sector, beyond its role as a global workbench. In A.T. Kearney’s ‘Global Cities Report’, the performance of Shenzhen has been lacklustre since 2012, even retreating in the middle field in terms of ‘outlook’, comparing with a strong dynamism of other Chinese cities newly included in the ranking.

The pilot study concentrates on one specific question, namely whether Shenzhen evolves its own cultural characteristics and dynamism, combined with creating a sustainable and harmonious social structure that is embedded into this local culture. It is based on in-depth case studies, embedded in expert interviews and analysis of other sources, such as newspaper reports. Methodologically, it combines anthropology and economics, and mobilizes recent conceptual innovations in international China studies.

In common pictures of Shenzhen, the image of an ‘instant city’ prevails, driven by huge and historically unique inflows of migrants within a very short time. This short history of immigration has shaped its social structure, which is even reflected in the urban infrastructure and settlement patterns, with the ‘urban villages’ being the most conspicuous phenomenon. In the urban villages, where about 50 percent of the urban population live, migrant populations have met with the local inhabitants of the rural areas where Shenzhen was implanted. Even though those local people now only form a tiny minority in the total population, they are becoming increasingly visible in the ongoing renewal of urban villages, with many expressions of traditional culture embodied in artefacts, buildings or public events.